Books

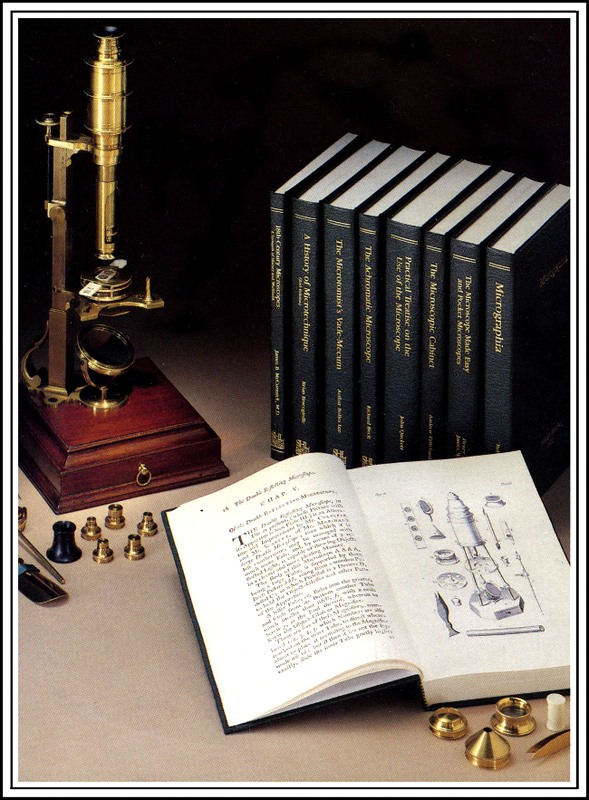

![]() Our History of Microscopy book series is a collection of eight volumes selected from both classic literature in the field of natural science technology and new manuscripts. The selection of titles does not judge other important works to be of less consequence, but rather it accounts for a sampling of literature that spans three centuries of inquiry. We present them in fine bindings reminiscent of a time when bookmaking was an art. If you have ever wondered how the microscope evolved, how minute objects were described as they were viewed for the first time, how specimens were prepared, problems were solved, and new discoveries were achieved, then the Science Heritage History of Microscopy series and library will provide a rewarding experience.

Our History of Microscopy book series is a collection of eight volumes selected from both classic literature in the field of natural science technology and new manuscripts. The selection of titles does not judge other important works to be of less consequence, but rather it accounts for a sampling of literature that spans three centuries of inquiry. We present them in fine bindings reminiscent of a time when bookmaking was an art. If you have ever wondered how the microscope evolved, how minute objects were described as they were viewed for the first time, how specimens were prepared, problems were solved, and new discoveries were achieved, then the Science Heritage History of Microscopy series and library will provide a rewarding experience.

The Microscopic Photographs of J.B. Dancer, a 288 page, 9×12 inch deluxe bound volume of photographic art, is of special importance to those who are interested in photography, science, and social history. Each of the J.B. Dancer atlas pictures is accompanied by informative notes that form a fascinating portrait of the taste and interests of the 19th Century.

The Atlas Catalogue of Replica Rare Ltd. features a collection of twenty rare microscopes (c. 1675 to c. 1840). Each microscope portrait includes all of the instrument’s important attachments and accessories. Along with each microscope is an eloquent description written by the 1975 President of the Royal Microscopical Society and Associate Curator of the Museum of Science at Oxford University, Gerard L’E Turner. An introduction to the collection and chronological history of microscopes is offered by J.B. McCormick, M.D.

The book, Notes on Nursing by Florence Nightingale was first published in 1860. Treasured by nurses, this practical and witty guide to the healing arts is an exact replica of the first 1860 edition, hand-bound and gold embossed. Certainly of historical importance, these “notes” remain relevant to the healing arts as they are practiced today.

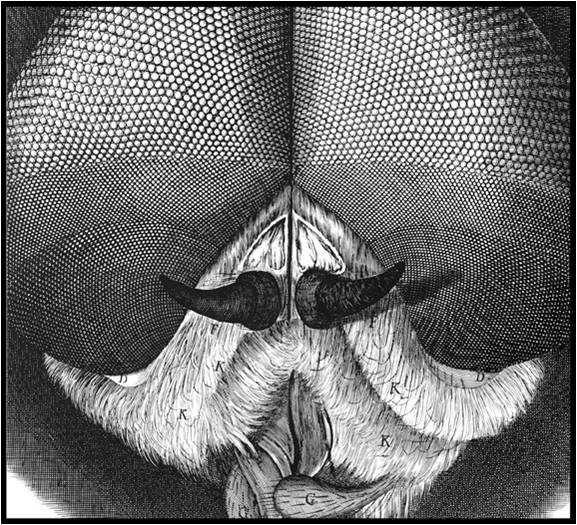

Micrographia by Robert Hooke (1665)

A facsimile edition of Robert Hooke's most profound work, Micrographia includes minutely detailed descriptions, philosophical queries, and beautiful engraved illustrations. The book was authorized on November 23, 1664 by the Council of the Royal Society of London for the Improving of Natural Knowledge.In the dedication "TO THE KING" the author pays homage to a monarch who, by power and right, ruled over all aspects of society - both individual and collective. Hooke acknowledges that "philosophy and experimental learning have prospered under royal patronage," yet places them in perspective with the "nobler matters: the improvement of manufactures and agriculture, the increase of commerce, and the advantage of navigation."

Hooke's philosophy is clearly revealed in the opening words of the preface: "It is the great prerogative of mankind above other creatures, that we are not only able to behold the works of nature or barely to sustain our lives by them, but that we have also the power of considering, comparing altering, assisting, and improving them to various uses." Hooke calls attention to the need of "rectifying the operation of the senses, the memory, and reason." He then explains how this can be accomplished; The senses can be expanded through the extension of sight by the use of his newly designed and improved microscope; The memory is improved with his minutely detailed engraved illustrations; And the power of reason is demonstrated by recording his observations and queries, thereby revealing scientific truths and facts.

Beginning with chapter 1, Hooke systematically examines common materials and compares the unaided view with the expanded view of the magnifying glass. He notes the imperfections of man-made objects, and contrasts them with the infinite perfection of natural objects. Hooke applies his scientific method to the properties of matter, from solid to fluid. He deducts that fluidity is a property given to finely divided matter and that solubility is a property of like matter and density, i.e. oil and water. He concludes that fluidity is like fine sand vibrating on the head of a drum. A piece of cork will float to the top of the energized sand particles, while a piece of lead will move to the bottom. Hooke never ceases to observe. Whenever his eyes were open, the world around him was a laboratory. Whatever was at hand, he observed its properties. If it was snowing, or there was frost on glass, he observed the flakes and crystals. In this book, Hooke questions form, origin, and the relationship of one observation to another as he examines, describes, and comments upon a broad variety of mineral, plant and animal materials. Micrographia is a fascinating and rewarding account of a significant time in scientific history. Price: $75.00The Microscope Made Easy by Henry Baker (1769) and Pocket Microscopes by James Wilson(1706)

These impressive works review the state-of-the-art in eighteenth century microscopes. Baker wrote to those who "desire to search into the wonders of the Minute Creation, tho' they are not acquainted with optics." He includes complete directions on "how to prepare, apply, examine and preserve all sorts of objects: and proper cautions to be observed in viewing them." In first presenting he book to the Royal Society of London on October 28, 1742, Baker wrote that his goal was to "attempt to excite in mankind a general desire of searching into the wonders of Nature." Baker's descriptions of many microscopic objects must certainly have left some readers of the time in disbelief.

The Microscopic Cabinet by Andrew Pritchard (1832)

This book describes Pritchard's studies of the biology and anatomy of minute organisms. Is also includes a stimulating account of the author's experiments with precious jewel lens systems in his attempt to perfect and color correct the optics of the microscope. In the preface, Pritchard provides an excellent summary of the book. "While almost every part of nature has within the last few years been explored, and our knowledge augmented, the living objects described in this work, have been nearly overlooked by naturalists, and such representations as we possess of them are delineated in the most incorrect and grotesque manner that can well be conceived; for these reasons the Author has presumed to call the attention of the public to this interesting branch of natural history."

Practical Treatise on the Use of the Microscope by John Quekett (1848)

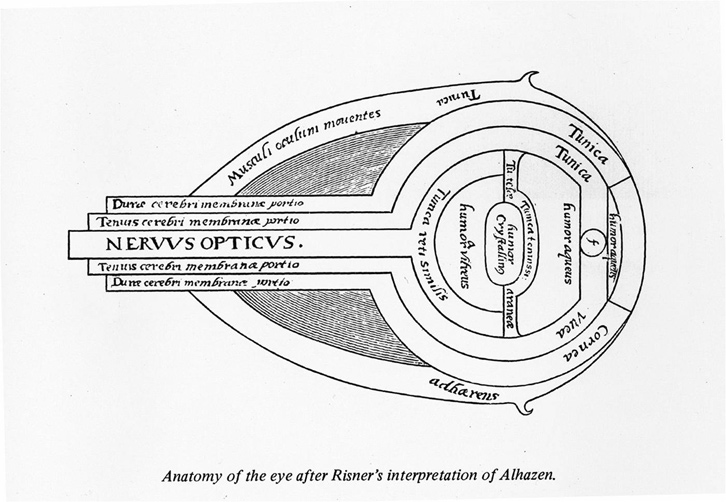

Quekett provides an authoritative history of the microscope from ancient times to the perfection of the achromatic lens... This book is a classic of the mid-19th century and a model for contemporary text design. In the Preface, he acknowledges the importance of the microscope as an instrument second only to the telescope. He also expresses the need for a generalized book of instruction applicable to any instrument. Finally, he attributes the extensive sections on microscopical specimen preparation to his own experience and expertise. The book opens with a 46-page history of the microscope that perhaps is one of the most accurate and detailed ever written.

An excellent review of ancient literature traces the history of the magnifying lens, or burning lens, from Aristophanes in 500 B.C. to Seneca in A.D. 65, Pling in A.D. 79, Ptolemy in A.D. 100, then on to Bacon in 1551, Fontana in 1618, and Drebbel in 1621. Quekett then moves on to the celebrated Robert Hooke in 1667, discussing the work presented in Micrographia. He then weaves an accurate and well-written history of the development of the microscope through the next 150 years. The author's valuable and lucid chronology for the solution to chromatic distortion in the objective lens systems of the compound microscope is a classic.

He relates that this problem was first described by Chester More Hall of Essex in 1729. In 1747, Euler experimented and produced an achromatic object glass. In England, Dollond was stimulated by the work of Isaac Newton on color dispersion of white light to do experiments that produced color corrected telescopes but not microscopes. Chevalier, in France, reported on a 1774 article from St. Petersburg that provided detailed instruction to form an object glass of three elements the first and third of crown glass and the second of flint. Further, Quekett relates that in 1812, Sir David Brewster rendered both simple and compound instruments achromatic by the use of an immersion oil bridge between the objective front lens element and the specimen being examined, and at about the same time, Professor Amici of Modina was experimenting to improve the image. His work passed on to Goring and Cuthbert, who improved upon his design by producing a reflector-based achromatic microscope. Finally, Quekett reports that in 1829, Joseph Jackson Lister Esq. read his paper to the Royal Society in which he described the method of making the most improved achromatic objective lens systems. This book then describes a number of microscopes and instruments using beautiful woodcut illustrations. Detailed descriptions of the rationale and function for each instrument are also provided. Part two of this treatise provides detailed instructions on the use of the microscope. Quekett explains how to create optimum illustration with carious lenses, substance conditions, and lamp relationships. He then provides various methods for preparing specimens for microscopic examination. This book is a classic of the mid-19th century and a model for contemporary text design. Only 17 left! Price: $75.00The Achromatic Microscope by Richard Beck (1865)

The author of this treatise writes in great detail on the construction, proper operation, and capabilities of Smith, Beck, and Beck's achromatic microscopes and accessories. It is a rare description and detailed instruction on the use of an advanced design achromatic microscope and numerous special accessories. He begins with a description: "A Compound Achromatic Microscope consists essentially of two parts, an object-glass and an eyepiece - so called because they are respectively near the object and the eye when the instrument is in use.

The object-glass screws, and the eyepiece slides, into opposite ends of a tube termed the 'body', and upon the union of the two the magnifying power depends. The microscope-stand is an arrangement for carrying the body; and is combined with a stage for holding or giving traverse to an object, and a mirror or some other provision for illumination." He then describes each part individually: Microscope Stands, The Stage, The Mirror, The Substage, Revolving and Folding Bases, The Eyepiece, The Object-glasses, The "Universal Screw", and The 1/20th Object-Glass.

Beck goes on to describe the proper operation of the microscope, beginning with the management of light. He explains the methods of transmitted illumination - how to use the mirror, the diaphragm, the achromatic condenser, tests for object-glasses, adjustments for high powers, tests with the Podura-scale, methods of measuring aperture, "lined objects" as tests, Nobert's lines, and oblique illumination. He then explains the methods of illumination from above - how to use the slide condensing lenses, the slide silver reflector, the Lieberkuhns, forceps, and the opaque disk-revolver. Beck continues by providing specific instructions on viewing test object such as the splinter of a Lucifer match, the Podura-scale, the tarsus of a spider, the feather of a pigeon, and the Arachnoidiscus Japonicus. Another section of the book discusses polarized light as applied to the microscope. Specific methods are detailed, including the use of Nicol's prism, the selenite plate, Darker's retarding-plates of selenite, Darker's selenite stage, tourmalines, polarizers for large objects, experiments with double-image prisms, and crystals to show rings. Beck also describes and explains Wenham's binocular body for achromatic microscopes. He defends binocular vision and praises Wenham for making a major contribution to microscopy. Sundry apparatus is also described, including live-boxes and troughs, the screw live-box, lever compressors, Wenham's compressor, reversible compressors, the frog plate, the camera lucida, micrometers, Quekett's indicator, double and quadruple nosepieces, Leeson's goniometer, Maltwood's finder, and microscope lamps and tables. In addition, Beck also discusses the third class microscope for students, the universal microscopes, and single microscopes and magnifiers. Finally, he describes various instruments used in preparing objects, instruments and materials used in mounting objects, and microscopic cabinets. This classic text is the most complete and detailed description of the component parts and functions of a "modern" compound microscope. Only 4 left! Price: $60.00The Microtomist’s Vade-Mecum by Arthur Bolles Lee (1885)

Lee presents an organized collection of 660 tested reagents and procedures for fixing, staining processing, mounting and demonstrating all manners of biological and histotechnological material as known up to the publication date of 1885. As Lee points out in the preface, the book provides "a concise but complete account of all the methods of preparation." The introduction explains the purpose of the book, which is to provide zoological scientists with a collection of microscopical methods to participate in a wide list of needs. It is intended to reveal additional information from the images of nature viewed or enhanced for study through the microscope.

A History of Microtechnique – SHL 2nd Edition by Brian Bracegirdle (1987)

As Bracegirdle explains in the preface, "This book sets down the main facts of the evolution of the microtome and of the development and of the development of histological methods. The basis of the work was a comprehensive survey of the large literature and full documentation has been provided in over a thousand references..." In addition, more than 40,000 microscopical preparations have been inspected and evaluated as a check on written accounts, as have some 55 microtomes: some of these were used to cut sections as they would have been when first introduced."

18th Century Microscopes: A Synopsis of History and Workbook by James B. McCormick, M.D.(1987)

This book concentrates on a significant period in the evolution of the microscope. As expressed in the Preface, "It is not the author's intention to offer yet another charge of the brigade to form a comprehensive history of the microscope, but rather to dwell in the middle period of its evolution, when both simple and compound instruments were influenced by many novel mechanical designs; all attempting to stabilize the image and improve resolution."

This book is important in understanding the assembly and function of many accessories or attachments to evolving microscopes.

McCormick begins with a brief, general history of microscopes of the 17th and 18th centuries. He discusses the significance of the microscope relative to the inventions of other machines and instruments of the period - especially the telescope.

In chapter 2, McCormick reviews the development of the concepts that relate to the optics of the microscope. He writes about magnification, refraction, diffraction and interference, refraction and dispersion, and reflection. "It is a curious fact," he states, "that nearly 300 years elapsed between the invention of the eyeglasses, which use lenses to improve the sight of the human eye, and the earliest production of optical instruments, the telescope and the microscope. The thought of making a small, short focal length, hard lens, which is what constitutes the simple microscope, simply had not occurred to anyone." In the next five chapters, McCormick talks about the development of the simple and compound microscopes. He focuses on the problems faced by both users and designers of these instruments, and the attempts to solve the problems by invention and, in some cases, by accident. He discusses the development of the compass microscope and the Lieberkuhn reflector. He continues with the evolution of the compound microscope, highlighting the contributions of Edmund Culpeper and James Wilson with their screw-barrel designs. McCormick then goes into some detail about the modifications that were applied to the basic designs. He discusses the Edinburgh Wilson Screw-Barrel Microscope, the Solar Microscope, the Double Reflection Microscope, and the Culpeper-type Microscope. Finally, McCormick describes the development in 1744 of the Cuff-type Microscope, which is the forerunner of the modern microscope. "Mechanically, this instrument is far superior to any of its predecessors. Its advent ushered in a new trend in microscope design. All major instrument makers copied or made slight alterations and modifications to Cuff's model. His fundamental structural plan prevailed for some 50 to 60 years." He closes with a detailed description and use of a Cuff Microscope. This book is important in understanding the assembly and function of many accessories or attachments to evolving microscopes. Only 8 left! Price: $60.00Complete Science Heritage Library Collection

The History of the Microscope library set of books was prepared to make the philosophical and technological heritage of microscopy easily accessible. The set consists of a collection of eight books – six rare facsimile editions of classic science literature and two recent works concerning the development of histotechnology and microscopy. The bound books are presented in an attractive slipcase.

The Atlas Catalogue of Replica Rara Ltd. Antique Microscopes (1657-1840)

After years of searching, the Directors of Science Heritage Ltd. assembled this collection of twenty rare microscopes (c. 1675 to c. 1840). Each instrument has been selected with great care to demonstrate the development of knowledge and technology during the important phase in the evolution of science. The collection has been reproduced in limited editions for collectors and museums in all parts of the world.

The Atlas Catalogue of Replica Rara Ltd. Antique Microscopes (1675-1840) is a rare book in time. This handsome and informative special edition includes twenty full page color portraitsof the complete Science Heritage Ltd. Microscope Collection. Each microscope portrait includes all of theinstrument's important attachments and accessories. Accompanying text description is written by Gerard L'E Turner, Associate Curator of the Museum of Science at Oxford University. An introduction to the collection and brief chronological history of microscopes is offered by J.B. McCormick, M.D.

Price: $47.50

Notes on Nursing by Florence Nightingale (1860)

The book, Notes on Nursing by Florence Nightingale, English nurse and founder of modern nursing, was first published in 1860. Treasured by nurses, this practical and witty guide to the healing arts is an exact replica of the first 1860 edition, hand-bound and gold embossed. Certainly of historical importance, these “notes” remain relevant to the healing arts as they are practiced today.

Microscopic Photographs of J.B. Dancer by Brian Bracegirdle and James B. McCormick

The Microscopic Photographs of J.B. Dancer features 265 of the 277 listed titles in the Dancer 1873 catalogue and a total of 388 from the combined Dancer-Suter lists. The 288 page, 9×12 inch deluxe bound volume of photographic art, is of special importance to those who are interested in photography, science, and social history. Each of the J.B. Dancer atlas pictures is accompanied by informative notes that form a fascinating portrait of the taste and interests of the 19th Century.

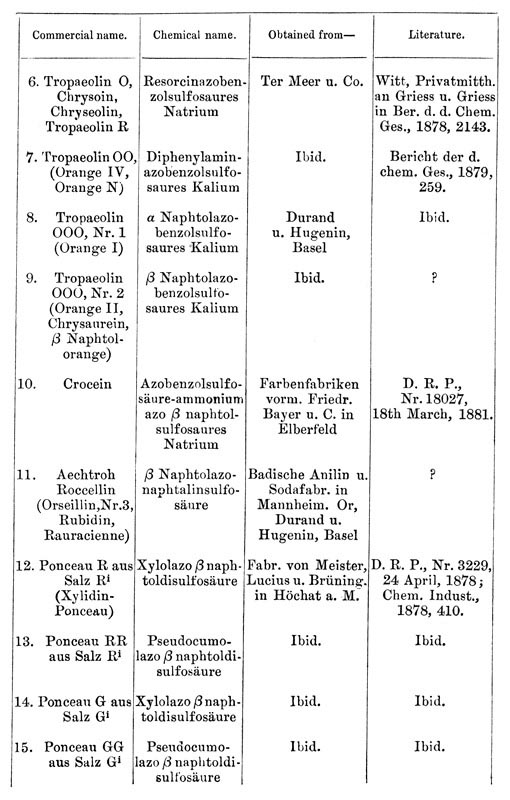

|

John Benjamin Dancer was an optician who lived most of his life in Mancester, England. He was distinguished as a lecturer/scientist and was the inventor of microphotography. The Dancer microscopic photographs averaged 1/8" in diameter and were produced as a scientific entertainment novelty to be viewed through a microscope or magnifying glass also produced and sold by Dancer.

The volume of The Microscopic Photographs of J. B. Dancer brings together for the first time a nearly complete representation of the of the 1873 Dancer collection. Also included are production slides and biographical information on each microscopic photograph. |

| |